A Wacky Road to Redemption: On Francine Prose’s “The Vixen”

published in the Los Angeles Review of Books

August 10, 2021

THE MOST SURPRISING thing about The Vixen, Francine Prose’s historical novel about the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, is how laugh-aloud funny it is. Prose manages to interpose her narrative of that terrifying night in June 1953, when news of the execution interrupted television programming, with an episode of I Love Lucy, so that the two Ethels — Mertz and Rosenberg — become entwined in a sort of madcap symphony of pathos. It is a testament to Prose’s mastery as a storyteller that what emerges is a penetrating look at the underside of comedy — namely, how the human condition can be so predictably cruel and paranoid.

And yet, this is also a book steeped in the warmth of Jewish family life, post–World War II. We learn about the Rosenbergs through the eyes of a feckless young Harvard graduate named Simon Putnam, whose life is built on a series of lies, starting with his name. “Putnam” was bestowed on his grandfather by an immigration official on Thanksgiving as a joke in honor of the holiday, when he was given the goyishe surname of a Mayflower pilgrim. In other words, assimilation is at its peak in America just as everyone is presumed to be a commie sympathizer and the two-martini lunch is in vogue.

Switching back and forth between sitcoms and Sing Sing, the action unfolds from the flickering, 12-inch black-and-white TV inside the Putnams’ cozy little Brooklyn apartment. On the love seat, Simon and his father, who sells ping-pong paddles at a sporting goods store, cannot believe what they’re watching. Nor can Simon’s mother, a teacher with chronic migraines who lies under a crocheted blanket on the nearby couch. She was a high school classmate of Ethel’s (just as the author’s own mother was), and she reminds her son about Ethel’s operatic voice, her clotheshorse ways, and her kindness. The repartee between the parents crackles as we learn that the state’s flimsy case against the alleged Soviet spies, especially Ethel, hinged on a torn box of Jell-O. “She should have stayed kosher,” his mom quips — meaning that, since observant Jews don’t eat Jell-O, her life might have been spared.

But then, we see that the ghastly execution didn’t quite stop Ethel’s heart, requiring extra jolts of electricity. To Simon’s mother, this simply meant that “her heart kept beating for her boys.” When two doctors finally pronounce her dead, the question that arises is: “How is this different from Dr. Mengele?”

In truth, the Putnams’ fictional outrage over the execution mirrored a very real worldwide protest over the Rosenbergs’ execution. Albert Einstein pleaded with President Truman to pardon them. Pablo Picasso called their imprisonment “a crime against humanity.” Nobel Laureate Jean-Paul Sartre said that killing the Rosenbergs amounted to “a legal lynching which smears with blood a whole nation,” adding that America “is sick with fear.” Even Pope Pius XII asked President Eisenhower to spare the couple, but Eisenhower refused.

Still, the underlying heartbeat of The Vixen isn’t political so much as literary — a book within a book that keeps the narrative thrumming. Rejected from graduate school, Simon begins to understand that his Harvard degree has no currency other than bragging rights for his parents. He bides his time by riding the Cyclone at Coney Island, a 12-minute walk from his home that he can do with his eyes closed, “like a dog, by smell, into the cloud of hot dog grease, spun sugar, sun lotion, salt water.” The mechanical monsters and scary rides, though, are not scarier than Roy Cohn, one of Joe McCarthy’s hatchet men. Within a year, Simon’s uncle helps him land a gig as a junior editor, working through the slush pile, at a financially troubled book publisher. When Warren Landry, the head of the agency, assigns him an editing job on his first book, Simon is horrified to discover that the top-secret project he’ll oversee is a trashy novel about a sex-crazed commie spy who enjoys kinky sex with Russian agents.

The hope, of course, is that the book will do for the Rosenbergs what Scarlett O’Hara did for the Civil War, not to mention reviving the company’s bottom line. But when Simon realizes that the author of The Vixen, The Patriot, and The Fanatic is locked up in a loony bin on the Hudson, mystery-thriller vibes ensue: not only does the CIA want his book published, but his creepy Harvard professor might have had a hand in the operation, too. All roads lead back to his swashbuckling boss, a former OSS officer whose “diction and accent combined the elongated vowels of a New England blueblood with the dentalized plosives and flat a’s of a Chicago gangster.”

It’s a wacky road to redemption for the protagonist, who falls in love with every woman he meets in an era when breast size determines employment opportunities. Ultimately, Simon will need to overcome the shame he feels for his parents’ immigrant past, as well as his guilt for trying to turn a novel that crucifies the Rosenbergs into a best seller. Wolfing down another hot dog at Coney Island, he remembers a passage from a book whose title he can’t recall: “[E]verything in the world is beautiful except what we do when we forget our humanity, our human dignity, our higher purpose.”

Francine Prose’s higher purpose as a novelist is fully realized in this delicious coming-of-age story in which everyone is afraid, anyone can be accused, and disinformation runs rampant. This novel also comes at a perfect time in American history, as hard-won voting rights are being suppressed and the fabric of democracy itself torn apart. Prose deftly reminds us of a chapter from nearly 70 years ago, during the Red Menace hysteria, when the government could jail and kill a couple for passing on secrets to the Soviets. Or, in Ethel’s case, for typing them up for her brother.

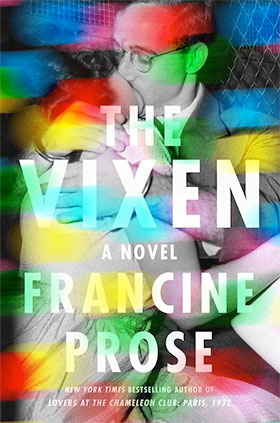

The Vixen is the kind of book that made me long to learn more. So, I watched the 2004 documentary Heir to an Execution by the Rosenbergs’ granddaughter, Ivy Meeropol, who tells the story behind the arrest, trial, and execution. Raised to believe in her grandparents’ innocence, Meeropol zeroes in on interviews and declassified government documents from 1995 that offer a more nuanced look at her family’s past, including Julius’s communiques with the USSR. What she also uncovers is a question that can never be answered: how could two loving parents knowingly turn their sons into orphans? Like the famous photograph of the Rosenbergs that adorns the front cover of Prose’s book — a big, smoochy kiss from the paddy wagon — love and secrecy will forever define their story.

¤

published in the Los Angeles Review of Books