published in the Los Angeles Review of Books

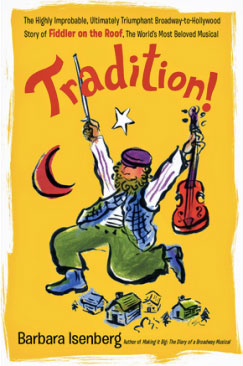

Tradition!: The Highly Improbable, Ultimately Triumphant Broadway-to-Hollywood Story of Fiddler on the Roof, the World’s Most Beloved Musical

WHEN FIDDLER ON THE ROOF first opened on Broadway 50 years ago, the New York literati hated it. Novelist Philip Roth called it “shtetl kitsch,” writer Cynthia Ozick said it was an “emptied-out, prettified romantic vulgarization” of literary master Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish tales, and New York Times theater critic Walter Kerr deemed it as “a very-near-miss.” But eight years and more than 3,000 performances later, Fiddler became the longest-running show on Broadway. By the time Norman (“What would you think if I told you I was a goy?”) Jewison was casting his 1971 film version of the musical, Frank Sinatra campaigned to play the lead of Tevye, the milkman.

Imagining the possibilities of a bearded Ol’ Blue Eyes singing “If I Were a Rich Man” with “glued-on payes” is among the many pleasures in Barbara Isenberg’s Tradition!: The Highly Improbable, Ultimately Triumphant Broadway-to-Hollywood Story of Fiddler on the Roof, the World’s Most Beloved Musical. It is impossible to read this affectionate chronicle of the making of the musical and film versions of Fiddler without summoning one’s own embarrassing recollections along the kvelling to farklempt continuum, where “Sunrise, Sunset,” arguably the world’s most sentimental song, takes center stage. Mine, culled from the annals of stage motherhood, occurred in a funky community center in Culver City where my then 12-year-old daughter starred as Golde in a kids’ production of the musical. Something about the shmatte on her head and her braces glistening in the floodlights reduced me to a blubbering mess: I don’t remember growing older, when did they? And she wasn’t even engaged yet.

Tradition! is an unapologetic valentine to the show, as its subtitle makes clear. But Isenberg, a former Los Angeles Times staff writer specializing in the arts, draws on three years of reporting plus earlier interviews with key players to offer a fresh look as to why Fiddler — ultimately a story about Eastern European Jews who must flee their homes — has maintained its universal appeal: every scene in it relates to the way culture is always in flux, to the way people simultaneously hold on to and let go of tradition in order to live in the world.

Isenberg includes both the macro and micro stories. Initially, investors, particularly Jewish investors, feared the show would be considered “too ethnic,” meaning “too Jewish.” Later, with Rosie O’Donnell starring in a Broadway revival, it wasn’t Jewish enough — “A Cozy Little McShtetl,” according to New York Times critic Ben Brantley. But that is part of Isenberg’s larger point in telling the tale: Fiddler’s longevity is as much a reflection of the acceptance of Jewish life in American culture in the past 50 years as it is a story about a father who must come to terms with losing his daughters as they claim their freedom from home.

And, Isenberg writes, at its core the show is about a world in turbulence:

Fiddler has become a sort of tabula rasa for terrorism, repression, and prejudice that seems eternally pertinent. Warning that “horrible things are happening all over the land” could apply to Nazi Germany, Vietnam, or Iraq as much as to pre-revolutionary Russia. So could Tevye’s rejoinder to hearing “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”: “And that way, the whole world will be blind and toothless.”

Isenberg dates the first meetings about the show to 1961, when lyricist Sheldon Harnick and collaborator Jerry Bock met with playwright Joseph Stein about how to adapt Sholem Aleichem’s stories as a musical. Stein wrote five drafts of the book, and the songwriters cranked out 50 tunes, of which one-third were actually used. Among the songs that were tossed out were two of Harnick’s favorites: “A Butcher’s Soul” and “Dear Sweet Sewing Machine.” By the time the perfectionist director and choreographer Jerome Robbins pared down the show even further, the reaction of out-of-town audiences helped to refine it more. As so often happens, two numbers that became hallmarks of the show were added out of town: “Do You Love Me?” Tevye’s plea to his difficult wife, Golde, emerged in Detroit; Robbins’s high-strutting Bottle Dance was finalized in Washington, DC.

The backstage backbiting between Zero Mostel, who had been blacklisted for not cooperating with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and director Robbins, who named names, is legendary. Mostel referred to Robbins as “Loose Lips” when the two had worked together two years earlier on A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, but they agreed to bury the hatchet when Mostel famously said, “we of the left do not blacklist.” For Fiddler, though, they barely tolerated each other, especially when Mostel made a point of vamping it up onstage and kibitzing with audience members in the front row.

For me, Tradition! is especially fun when Isenberg draws on interviews from lesser-known original cast members. Rosalind Harris, for example, was Bette Midler’s understudy in the role of Tzeitel, Tevye’s eldest daughter. When she heard about auditions for the movie, Harris tells Isenberg, Midler practically shooed her out the door: “Bette said, ‘Get your tush down there.’” Harris got the role. By the time filming began, Harris and the other actresses playing Tevye’s daughters had made a pact to stop shaving their armpits in solidarity with European women. But director Jewison saw them leaning back on a bed in one scene and yelled, “Stop! Cut! … Take them off the set! Shave their pits!”

How did Chagall’s famous painting of a rooftop fiddler inspire the show’s title? How did Jewison convince virtuoso Isaac Stern to play on the film’s soundtrack? Isenberg answers these questions with enormous care and deliberation. She is slightly less attentive to the question of what Fiddler’s legacy is in American musical theater, leaving former New York Times drama critic Frank Rich to fill in the blanks as he positions Fiddler within a sort of triad with West Side Story and Gypsy and suggests that these constitute “the serious stuff that was propelling the musical theater forward.”

Isenberg sounds the same note too many times, at least for this reader, when she quotes a theater producer from the Midwest saying, “If you are running a theater and you want to make money, Fiddler is a shoe-in: It’s a show people always want to see.” It’s a little like saying diamonds are pretty because they sparkle.

For fans of the show this is an especially rich reading year. Capitalizing on the show’s 50th anniversary, Picador rereleased in paperback last year’s Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof by Alisa Solomon. Where Isenberg never strays far from Broadway, Solomon’s is a more culturally complex look at the Fiddler phenomenon, starting with a rich introduction to Solomon Rabinovich, the writer from Kiev who took the name Sholem Aleichem as a political act (just as when Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali) and to advance the form of Yiddish literature. Solomon, whose language is of a more scholarly bent, also takes us to productions of the show in Poland, Israel, and a multiracial high school in Brooklyn, all as a way of demonstrating how Jewish cultural identity is felt and perceived around the world.

Isenberg, too, reminds us why audiences from Japan to Finland and 128 other countries continue to see the show, again and again. “I’ve played the show in San Francisco, Fort Worth, Atlanta and Toronto,” says actor Harvey Fierstein.

I’ve played it all over, and the reaction is the same. When I was on Broadway, I’d look out into the house, and there would be Hasidic Jews and nuns or maybe a high school cheerleading team in town for a competition, and they all sat with rapt attention watching it. They all got it. Fiddler goes directly to the heart. The show reaches you, no matter who you are or where you are in your life. It changes with you.

¤

published in the Los Angeles Review of Books