published in the Los Angeles Review of Books

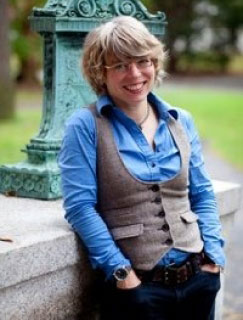

SMALL AND ATHLETIC, Jill Lepore zips into her second-floor office at Robinson Hall in Harvard Yard, wearing a neon-green cycling jacket. At 47, the chair of Harvard’s history and literature department and prolific New Yorker staff writer speaks in the clipped, rapid-fire cadences usually associated with undergraduates, as if ready at any second to be interrupted. Her exuberance precedes her, from her tomboyish gait to the way her shaggy blonde bangs spill over her eyes in sheep dog fashion. It is no wonder a Jezebel blogger has recently crowned her “an irresistible bad ass.”

An unlikely historian, Lepore is a former field hockey player who was admitted to Tufts on an ROTC scholarship. By her own reckoning, she was the first member of her family to go away to college, and then she “just kinda fell into history.” Hers is a “goofy story,” she says, including the moment when a letter from her past would change the trajectory of her life forever.

An unlikely historian, Lepore is a former field hockey player who was admitted to Tufts on an ROTC scholarship. By her own reckoning, she was the first member of her family to go away to college, and then she “just kinda fell into history.” Hers is a “goofy story,” she says, including the moment when a letter from her past would change the trajectory of her life forever.

Much of Lepore's writing focuses on what’s missing in the historical record. Her previous books include The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death (Knopf, 2012); The Story of America: Essays on Origins (Princeton, 2012); and New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan (Knopf, 2005), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Her latest book, Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, was recently published by Knopf.

Jane Franklin outlived 10 of her 12 children. The truth of Jane’s life is the truth of what it means to carry, nurse, feed, clothe, teach, worry for and then bury your children, over and over. It is a story that rings true for so many women, even today, including myself. It took nine pregnancies, including two stillborn babies, for my husband and me to create three healthy children. And find the grit to go on.

Jane Franklin’s “quiet” story, as Lepore calls it, tells us what it means to bury a child and endure. It also speaks to Jane’s fierce intelligence and pragmatism, born of heartbreak. And it reminds us of the beauty of an “ordinary” life, one in which reading books and writing letters take center stage in the creation of a radical mind. Lepore’s scholarship of what’s missing from the historical record — and why — is a stunning reflection on the meaning of history itself.

— Joy Horowitz

You say that Jane Franklin’s obscurity is matched by her brother’s fame. Is that because she’s too busy taking care of everyone?

The differences in the lives of this sister and brother are marked by materiality. We always say that Ben’s was a rags-to-riches story as if that were a metaphor, but that is literally true. People would bring their rags to Franklin’s shop and he’d buy them and he’d use them to make paper. Then he’d use that paper to print money. Franklin literally turned rags to riches! He was the largest paper mill owner in the colonies, the most important printer of money. Jane’s life is rags-to-rags; she’s forever doing drudgery. I mean, we think of housework as a pain. And it is. But it’s not drudgery in the sense it was in 18th century when doing the wash took days and was physically grueling and in some cases quite painful. Her daily life included every kind of rag — for diapering, menstruation, for cleaning, for washing.

You write that Ben Franklin’s story is an allegory of America. How is Jane’s story an allegory?

I think her story is allegorical in that it helps us to think about inequality. If people go around with the idea that the only people in the 18th century were John Adams and George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, then they are left with no ideas at all about inequality. The historical record is profoundly uneven and asymmetrical. These men left behind so many documents, so much paper, and these other people did not. So Jane’s life works as an allegory that reveals persistent forms of inequality, and what is more urgent to understand than inequality?

I took on a fairly ambitious sense of mission when I finally decided to finish this book — which I tried for many years to write and kept abandoning. I wanted to tell Jane’s story as a way to ask readers to think about how history gets written: what gets saved and what gets lost, what gets remembered and what gets forgotten, and what the consequences are of each of these choices.

Franklin writes an autobiography in which he leaves Jane out — the person to whom he wrote more letters than to anyone else. He never mentions her name because he’s crafting a story about himself and about anybody that’s worthwhile, anyone who is unencumbered and can pursue their own individual freedom. Her story is not that. Her story is about taking care of her children, her grandchildren, her great-grandchildren — taking care of anybody but herself. We need that piece of the story.

That they are siblings makes the inequality in their lives very moving.

It’s organic to the 18th century — the idea that a relationship between a brother and a sister is particularly illuminating. In 1790 the American writer Judith Sargent Murray writes this essay about the inequality of the sexes using a standard enlightenment thought experiment: What would happen if we followed a pair of twins, a boy and a girl, and we followed them throughout their lives. The boy would be rewarded for all his spirit of adventure and his interest in reading and writing and the girl would be told not to do any of those things. That thought experiment has been conducted again and again by feminist writers, most famously by Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own when she wonders: what if William Shakespeare had a sister Judith? She tells the story you’d expect, about the stunting of the girl. William’s sense of adventure gets rewarded; her sense of adventure gets her pregnant. At 15. And she feels she has to kill herself.

The great thing about Jane Franklin’s story is that it’s not a thought experiment. It really happened. She doesn’t kill herself when she gets pregnant. She has 12 children and she raises the grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She endures. She persists in spite of inequality. For all the narrowness and stunting, she travels an incredible intellectual journey. She transforms from this devout Puritan girl in Boston — her duty is to submit, which is all a girl is taught — to a woman with ideas about natural rights and a need to have more smart people around her. Couldn’t somebody please send her more books? And isn’t it obvious that people who don’t get an education are treated unfairly? She’s quite a radical by the end of her life.

She’s not Mary Wollstonecraft. She’s not a learned lady or a lady of letters. She’s the most ordinary of people. And yet reading and absorbing the political and philosophical ideas of the 18th century, she becomes a revolutionary in her own way. She doesn’t write about the inequality of the sexes. It’s poverty she’s angry about.

You have to talk about the Queen of Sluts.

There’s this 18th century artist named Patience Wright. She’s got, I think, five children. She plays with her children all the time. She loves to make things. When she’s making dough she’ll make little heads out of dough. She’s quite a talented sculptress. Her husband dies. She decides she has to support herself. So she begins making wax figures, kind of like Madame Tussauds. But she has a very distinctive method.

Just picture an 18th century woman with her big skirts. She puts the wax beneath her skirt, between her upper thighs to heat it up. She needs the wax to be soft and warm. And then — don’t film me doing this — her hands start working under her skirts and, without looking at what she’s doing, she forms the figure she’s making a likeness of. She’s doing this while sitting with her subject. Like, she’ll be sitting with William Pitt. Or Benjamin Franklin. Or the King and Queen. And she pulls from her skirt a life-sized figure. This is how it’s described in the accounts. The engravings are meant to be smutty. The whole thing is both fascinating and scandalous all at once.

It’s hard to believe this is what actually happened, but Patience Wright pulls from her skirts a bust of William Pitt from his head down to his navel, so it looks like they’re in an act of congress. And Jane Franklin thinks this is like the coolest thing she’s ever heard of. Her family is a soap and candle maker. So she works with wax all the time.

With her children in tow, Patience Wright goes on a tour of the colonies to display and sell her work. And everything about this, as you can imagine, is speaking to Jane. Or at least I can imagine it speaking to the Jane that I know. And so Patience Wright comes to see her. And she asks her to write a letter of recommendation for Jane to send to her brother. People are always asking Jane for a letter of recommendation to Ben Franklin. But in this case, Jane writes one. “Patience Wright is a very talented artist and I think you should do her a favor and sit for her.” And she sends it to Franklin in London.

Franklin sits for Wright in London, and she soon she is fashioning likenesses of members of court. And then she becomes a spy. Patience Wright is her own fantastic story. Someone asked me in a public lecture, “Did Jane Franklin know Abigail Adams?” I laughed and said, “Nor do I know Hillary Clinton.” They’re in different social worlds. Jane was a poor tradesman’s daughter. A widow. Abigail Adams goes on to be the wife of the president. She’s a much more learned lady. The difference of their sensibilities is what we’d call a class difference. Abigail Adams called Patience Wright “The Queen of Sluts.” To Abigail Adams that was a completely grotesque and smutty thing to do. Whereas Jane just thought it was great.

I loved that, when he asked her to, Jane made soap and sent it to her brother in Europe to help him play the role of a country bumpkin.

When Franklin went to Paris to negotiate the French Alliance during the Revolutionary War, everybody adored him there. He didn’t speak French particularly well but he did speak it. And of course he’s very, very funny. A lot of Franklin’s humor is quite filthy, as you may know. John Adams was utterly scandalized by Franklin’s behavior in Paris; he had all kinds of paramours. He led this very cosmopolitan life. What he did while in Paris was cultivate the image of himself as a rustic, because he was a very clever man and he knew that in the fashionable Parisian world this would make him stand out — to be a bumpkin. This is what the French thought about Americans in the first place and they would enjoy being found to be right. Have you been to Paris lately? They still think that.

It was a good game to play. And Franklin would dress in a way that he would not dress at home; he wore home-spunny clothes and a goofy coon hat. So he’d crab around in his spectacles and coon hat and would play the rustic. And it worked because he and Jane were born into a very poor, very ordinary, very obscure family in Boston. In the very beginning of the century, their father worked as a candle maker. Which works very well as a metaphor for the enlightenment, right? It’s like Franklin brought the candle to the dark obscure corner that was Boston. Then he harnessed lightning with electricity! The whole metaphor of bringing lightness into darkness was a big piece of it.

Franklin emphasized the lowliness of his origins in order for his rise to be all that more dramatic. Meanwhile Jane is still stuck in that lowly life, and that is one of the great ironies of their story. His attachment to her is partly that she’s very useful to him. Politically useful. He asked her to send him some soap. She’s the only one in the family who had the recipe. The woman’s got enough to do. She’s gotta make barrels of soap for Franklin as well? He instructs her, “Make sure it’s not too fine.” He wants the crumbly greenish stuff. Then he gives it away to the nobility in Paris as a badge of his homespun self.

I was fascinated by how you connect Jane to Virginia Woolf.

Virginia Woolf writes the Judith Shakespeare essay in 1928 based on a lecture she gave to the women at Cambridge University: What would have happened if William Shakespeare had a sister? It becomes part of A Room of One’s Own — a hugely influential essay. I became fascinated when I realized that Jane’s papers found their way from Boston to London and in 1928 were auctioned off by Sotheby’s of London. The auction catalogue survives with an entry describing this remarkable collection of letters from Benjamin Franklin to his beloved sister, Jane. The catalogue was circulating in London bookstores, in the world that Virginia Woolf inhabited, in 1928.

Everything Virginia Woolf is writing at that time — her diaries, Orlando, her essay “The Lives of the Obscure” — is about her interest in the lives of the obscure, the sisters of famous men, the relationship between fame and obscurity. Her father is the founding editor of the Dictionary of National Biography. It’s a biography of somebodies. She’s obsessed with biographies of nobodies. If that catalogue had conceivably come before her eyes, she would have been fascinated by the collection of Ben Franklin’s letters to Jane — and that’s just when she comes up with this idea to write an essay about William Shakespeare’s sister.

I recently was giving a lecture at Stanford and went out to dinner with a bunch of people from the Humanities Center and a few literary critics as well. One woman was a well-known critic. She said, “I don’t understand your Virginia Woolf thing. Of course she read the letters! Why are you hesitant to make that claim?” As a historian, I’m quite cautious about evidence, and I have a more empirical sensibility from a disciplinary standpoint than literary critics do or than a journalist would. I’d like to think there’s a direct relationship there, so I put it in the book but in a suggestive way: Isn’t it interesting that at just this moment in time these two things happened? But I couldn’t find anything in Woolf’s diary that said, “Went to Sotheby’s auction yesterday.” There was no smoking gun.

But on some level it doesn’t matter. The point is a lot of people in the 1920s are interested in the lives of the obscure. It leads into the 1930s Depression sensibility —think about the WPA, the stories of ordinary people, the American folk life projects, the romance of folk music.

You describe Jane as saucy, a “celebrated beauty.” Why don’t we know what she looked like?

We don’t have any portrait. She never sat for one. I was incredibly excited late in the project to come across almost by happenstance a portrait of her granddaughter, Jenny, who she raised. Jenny’s on the book jacket. It felt to me like a good proxy for her. It’s the closest I have. We have many portraits of [Ben] Franklin.

I’d like to know what she looked like, but, as a historian who likes to write about people who are unknown, I often don’t know how people looked. I’d like to know if she was strikingly beautiful because that does change a lot of things about one’s life. Much later, in the 1770s, Franklin says something about “we fat folk” in a letter to her. At this point, Franklin is quite fat and has gout. They teased each other about that.

When Jane died, she had in her house what the probate inventory describes as a child’s desk. There were no children living with her so it made me wonder, too, if she was a very small person. And somehow I wish I could know because when I imagine the physical stamina of Jane’s life — 12 children, taking care of your parents, your grandchildren, and then in your 70s raising your great-grandchildren — somehow picturing a tiny person would mean more to me. But I also know that I quite dislike being seen because, I think, more with women than with men intellectuals, a visual can define how people understand you. I don’t like, for instance, when newspapers put the author’s face next to the book review. I think readers make assumptions. So, in that sense, I don’t mind not knowing what she looked like.

You wrote in The New Yorker about how you almost abandoned this project. Could you talk about that and your mom’s role in prodding you to get back to finishing the book?

I abandoned the project for two reasons. One is the source materials are so scant. But two, the story is quite sad, and I found it to be a real challenge, narratively speaking. If you think about an X-Y axis and you have birth over here and death over there moving through time chronologically. On your Y axis is happiness and prosperity. You have Jane and Benjamin and they start down here. And then, Franklin’s life is like a straight rise. His world gets bigger. He gets wealthier. Love and success. And Jane’s life is out of ThePrince and the Pauper or Tale of Two Cities. And at some point, narratively, we need them to switch places. The reader wants them to switch places. And they’re not going to. And so, I just quit. I didn’t know how to satisfy the reader that needs the story to go in another direction, because the story is going nowhere for Jane. Narratively, it was really hard to contend with.

So, when I came back to it I reimagined the project. It now begins two centuries before Jane is born and ends two centuries after — I sorta stretched out the X axis. So now the whole curve of the story looks different. And it allows me to make the broader claims of writing history.

After I had abandoned the project, an editor from TheNew York Times asked me to write about it for the op-ed page. At the time Paul Ryan had just released the GOP’s new budget manifesto, “The Path to Prosperity,” which is an allusion to a pamphlet of Franklin’s called “The Way to Wealth” first published in 1758. Of course, “The Path to Prosperity” is about really restricting the federal government’s contributions to social programs, especially programs for women and children and programs involving contraception and family aid. It troubled me to think that Benjamin Franklin would somehow be enlisted to support this particular set of causes. In fact, “The Way to Wealth” is something he wrote to try to help Jane’s son when his printing business was failing. It was essentially an act of charity. I was amazed that this act of charity had been turned into a manifesto. So I wrote an op-ed called “Poor Jane’s Almanac.” It was a little chronicle of Jane’s life. And I got this flood flood flood of mail — “Oh, my God when is the book coming out? I need to know this story. I never knew Benjamin Franklin had a sister. And how can it be that people had 12 children. I never knew anybody lived like that.” People really wanted to know. So I thought maybe I should do it.

My mother, like many people’s mothers, gave up a lot to stay home and take care of her kids. She worked as an elementary school art teacher for most of the time we were growing up, but I was the youngest of her kids. (I wrote a New Yorker piece about this called “The Prodigal Daughter.”) She felt strongly from when I was a little kid that she wanted me to go out in the world and do things she hadn’t been able to do. She had to come home and take care of her mother from this big adventurous life she had. She raised us and did not pursue her career as an artist. She was a happy person. She loved taking care of us. She did like her work quite a bit. But she didn’t want me to be constrained like she had been constrained. It’s almost like she made a project stripping me of all my natural instincts. I’m a real homebody. I like to be home. I like to just sit and read a book. She’d forever be kicking me out of the house. “You have to try this now. You have to try that.” I didn’t want to go to college. She said, “You must to go to college.” When I told her years ago about Jane Franklin — we had grown up on Franklin Street, so there was a lot of Franklin stuff in our house — she said, “You must write that book. It’s so important. People need to know.” I told her I couldn’t possibly write that book. It’s a one-sided correspondence for 30 years. How can you write about the person who only receives letters? She said, “Oh, you can figure it out.”

She’d nudge me about it over time. My parents are more elderly than my friends’ parents. They had me pretty late. My father died in the beginning of 2012. I had done a lot of work on the book but by no means had finished it. I thought, “Oh shoot. I have to finish this now. I’ve waited too long.” I put everything aside and worked really hard to finish the book. But not in time. Because my mother died within the year.

But I do think of the book as a monument to my mother.

Living with Jane’s sorrow must not have been easy.

I wouldn’t say I’m a chipper person, but I’m easygoing and generally cheerful. And that person can’t write this book, right? You have to get in touch with the part of you that lives in agony to write a book about someone who suffers so much. Or else you’re going to trivialize it. That’s what cheap sentimentalism is, right? It’s someone who actually doesn’t understand sorrow. So, I had to go really spend time with that. What the reader response to that New York Times op-ed taught me was that sorrow is the story.

It was hard to dive down to the bottom of Jane’s sorrow because most of her sorrow was about the loss of her children. I have little kids at home, and when I’m snuggling with them in bed in the morning, well, it’s almost like you shouldn’t think about such a thing.

But at the same time I was going through a different kind of grief. When your parent dies, you have to rewrite the story of your life. Rethink your relationship to your siblings and your grandparents and your own children. You have to have a new story. You have to dive down to the bottom of your grief and that’s how you come out.

But I’ve heard from a lot of readers — readers who have lost children — who are grateful for that story being told. Whenever one of the various founding fathers loses a child, we read about it in a line or footnote. In all of these founding father doorstop biographies domestic sorrow is not part of the plot, as if it didn’t fell people to lose someone in the 18th century. Of course it felled them. But it’s not the story we want to tell about George Washington. So, it felt important to tell the story and make space for the profundity of grief.

I love your story about becoming an historian.

I had always wanted to be a writer. But how to get from where I was to a writer was a mystery that was insolvable. Some people in my family went to college but went to the local school and lived at home. I was the only person in the family who left home to go to college. And I only left home because my mother forced me to, just as she forced me to work as a kid. I had a gazillion jobs as a kid. Then I got an ROTC scholarship to go to school. I only applied to one school. I was in the Air Force. The Air Force doesn’t want people who are going to become writers. They need engineers, so I was a math major. I actually adore math. I was also a field hockey player. This was a serviceable sham in a way. This was a public version of myself I was happy to perform. The ROTC thing wasn’t arbitrary. I love the idea of public service of any form. It’s not contrary to who I am. But the deeper me is a voracious reader. I write maniacally pretty much constantly but I kept it hidden. So being in ROTC and a math major was another way of hiding.

Freshman year in college, my mother forwarded a letter in the mail that had come from me. I had forgotten this. Apparently, this is not an uncommon high school English assignment. I had this really terrific high school English teacher who had given us an assignment to write a letter to ourselves five years in the future. I had written this letter to myself. So I open it up. It was the scariest letter I had ever gotten. It was worse than a break-up letter. “Dear Jill: You are such a loser. I’m sure you’re doing things that have nothing to do with what you care about. You’re just pretending to do things you care about. Just fix it. Just get on with your life and do what you’re supposed to be doing.” A letter from a haranguing shrewish thing. Just imagine a 14-year-old yelling at you. I have that everyday at home. I know how scary a 14-year-old is. The righteousness. The black-and-whiteness. You just don’t want to hear from yourself at the age of 14. But it made me think, “Yeah, I am a total loser. I’m doing nothing that I care about.” So, I decided to leave ROTC. I quit the field hockey team. I dropped out of math and switched my major to English. I also broke up with my boyfriend, because I decided that also fell into the category of things that were stupid. It certainly did change my life. But, taking the longer view, what it really did was make me think about how the past speaks to the present. I was literally confronted by this voice from the past. I was fascinated that only five years had passed, but this document came from another era. Another person. And I had to really think hard to listen to this person.

People don’t write letters anymore, only emails. So preserving a record of our lives is questionable. How does that sit with you?

People don’t write letters anymore, only emails. So preserving a record of our lives is questionable. How does that sit with you?

I’m a dedicated purger. I delete everything. There seems to be evidence that this is the era that will be least documented in some ways. It’s sorta like a Dark Ages, because most of that stuff we write just goes away. That troubles me a great deal, but fortunately I’m not going to be around to write the history of this moment so that’s really someone else’s problem. If I were an archivist, that’s all I would be doing — trying to figure out how to solve this problem.

You write of the quiet beauty of Jane Franklin.

I like the idea that a life that was just a good life is worth writing about. You know? She didn’t accomplish some great triumph. She wasn’t Benjamin Franklin. We have biographies of people who did terrible, terrible things. And we have biographies of people who changed the world. I like the story of a good person struggling with the everyday ordinary chaos of living a life and doing well in the world.

Franklin published some essays as a young man under the pseudonym Silence Dogood. And that’s Jane.

Jill Lepore is the David Woods Kemper ’41 Professor of American History at Harvard University and a staff writer at The New Yorker.

published in the Los Angeles Review of Books